Printable version of the interview

Nancy Burns is the Associate Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs at the Worcester Art Museum, where she has organized eleven exhibitions, including Photo Revolution: Andy Warhol to Cindy Sherman and Rediscovering an American Community of Color: The Photographs of William Bullard. She was interviewed by Susan Schmidt.

SS: Could you describe your role as curator of the WAM collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs?

NB: As Stoddard Associate Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs I serve as the steward for WAM’s outstanding collection of pan-Atlantic works on paper. This includes exceptional holdings of Sargent and Homer watercolors and wonderful examples of early photography. As far as prints are concerned, WAM boasts remarkable holdings reflective of the history of color printmaking with emphasis on European color prints before 1900 and American color prints after 1900. Some of my personal favorites include our group of Mary Cassatt color aquatints, eighteenth century French prints by the likes of Philibert-Louis Debucourt, substantial holdings by Goya, and our mid-century American prints.

I consider the most important part of my job to be collection care. That surprises a lot of people who think that curators are mainly concerned with acquiring art and putting it on the wall. These are really important aspects of my work, but overseeing the storage and safety of the collection is my number one priority. Curators of works on paper are unique in the hands-on way in which we engage with our respective collections. At WAM, the pan-Atlantic PDP collection includes over 20,000 objects ranging from medieval art to the present. That’s a lot of pieces of paper to keep organized and safe. Other unique parts of my job include researching works in the collection, building exhibitions, and looking at potential acquisitions.

Philibert Debucourt, La promenade publique, 1792, color mezzotint, softground etching, etching, engraving, and roulette,, 53.9 x 72.6 cm, sheet, Mrs. Kingsmill Marrs Collection, 1925.154

SS: How does the WAM acquire prints for their collection?

NB: The acquisition process is different from museum to museum and gifts and purchases are treated somewhat differently. That said, here’s the basic process:

Once I’ve found an object I’d like to propose for acquisition I run it by the Director of Curatorial Affairs, Claire Whitner. This is especially important in the case of a purchase regardless of its cost. If she’s on board, then I work with our registrar to have the object brought onsite. Once it’s in the museum our paper conservator looks at the object and assesses the condition of the work with me. If everyone is still in favor of moving forward, I write a justification for the object and present it at an upcoming acquisitions meeting comprised of curators, registrars, conservators, the head of the education department, and the director. Thereafter, the work is brought to our collections executive committee, which is an outside governing body comprised of members of the museum. Finally, the Board of Trustees signs off on the recommendation of the collections committee. So, as you can see, it’s a rather cumbersome and lengthy process to add even one work to the collection.

SS: What is your conceptual framework for building the WAM print collection?

NB: In its history, there have been several curators of works on paper at WAM whom I admire immensely. As I’ve built exhibitions from our collection, I’ve realized how lucky I am that my predecessors thought about the PDP collection as encyclopedic in nature. That approach has made it possible to organize projects with wide-ranging narratives.

Keeping that in mind, no curator can fill every gap nor can she be an expert on everything. In my case, I’ve tried to pinpoint areas of WAM’s collection where our holdings are less robust and merge those areas with my own interests and strengths. In my case I’m pretty consistent in my love of process, regardless of medium. I tend to invest heavily in photographers who take a conceptual approach to photography and gravitate to experimental printmakers, especially those who are responsive to the socio-economic concerns of their moment.

For example, I mentioned that WAM has an exceptional collection of innovators in color printmaking. Now, I keep my eye out for color prints from the last 20 years that utilize contemporary technology in such a way that I can maintain that thread in our collection. Also, upcoming exhibitions have a significant impact on acquisition purchases. In my mind it’s always preferable to display work from our collection rather than seeking out a loan. In 2019, I did an exhibition called Photo Revolution: Andy Warhol to Cindy Sherman. Many visitors were surprised to learn that the exhibition featured nearly as many prints as photographs. In the year or so leading up to that exhibition many of the prints I acquired were geared toward display in that exhibition. For example, I acquired a Leon Golub lithograph, Edward Meneeley photocopies from the 1960s and a Dieter Roth collotype.

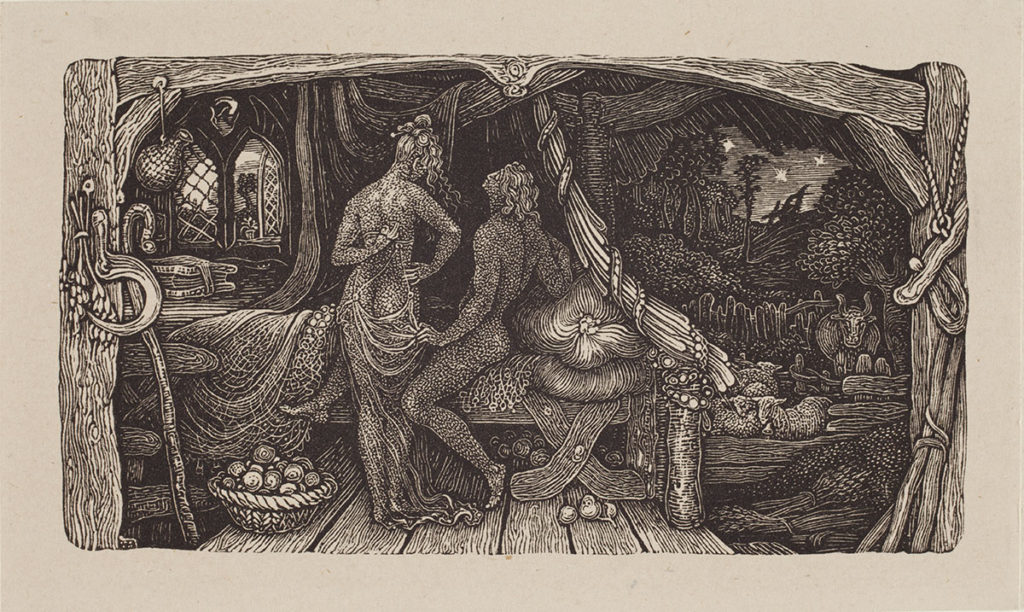

Edward Calvert, Chamber Idyll, 1893, wood engraving, 5.3 × 8.7 cm, sheet, Richard A. Heald Fund, 2016.5

SS: Who is underrepresented in the WAM print collection?

NB: First, every museum has examples of underrepresentation no matter how large the collection or how wealthy the institution. That’s because “underrepresented” means something different depending on who you ask. At present, underrepresentation at museums often refers to the absence or marginal presence of BIPOC artists in permanent collections. Underrepresentation has many other faces as well. Obvious examples are geographic underrepresentation and gaps with regard to important movements, genres, or styles.

Many unfamiliar with museums don’t realize that most collections, especially collections of works on paper, are primarily the product of gifts. As a result, most print collections

reflect the collecting tastes and interests of their donors over generations. So, if one’s donor base isn’t collecting something, then the only way to acquire that material is though purchases.

WAM is certainly among the many institutions reviewing their collections and seeking greater representation of African American, Latinx, and American Indian artists. I would say our print collection is in greatest need of additional Latinx and American Indian representation. Speaking to the pan-Atlantic world that I steward, South American artists are a lacuna as well.

South American art is a great example of the challenges a curator faces when trying to remedy gaps in a collection. Since the New England donor base generally does not collect South American prints, that’s not an especially fruitful avenue for soliciting gifts. Moreover, I’m not a specialist in the history of South American art, which puts me and the museum at a disadvantage in terms of determining the artists we should be targeting. Further, South American prints are scarcely represented at Northeastern galleries, dealers, and print fairs. This becomes an issue of access. If I can’t access that work within the means of my travel budget, there isn’t an obvious way to tackle the problem.

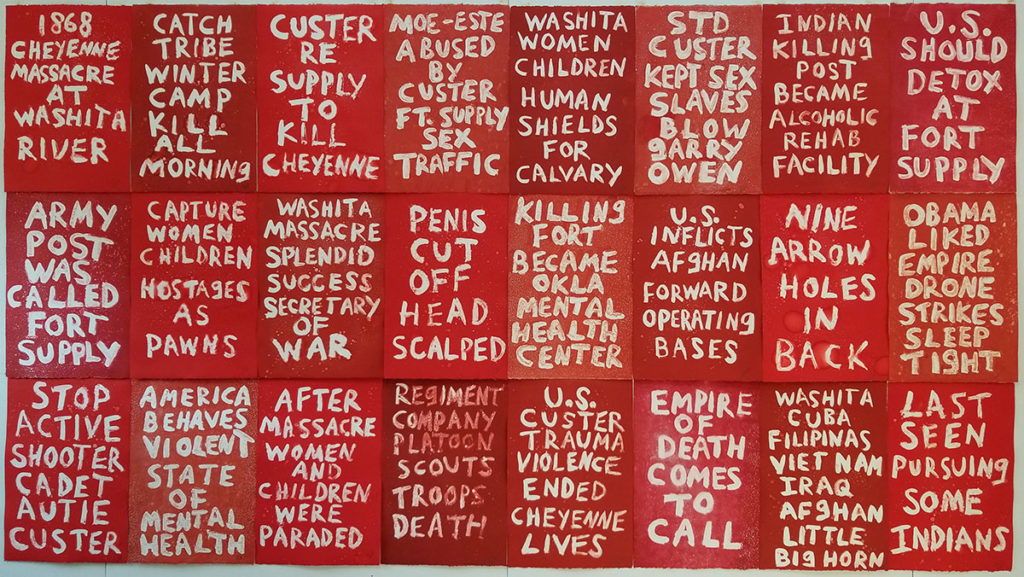

As far as my collection plan is concerned, I’ve tried to identify works for acquisition that hit multiple notes, such that a single object can address various gaps in the collection. For example, a few years ago I made a significant acquisition of a large-format photograph by the Canadian photo-conceptualist Stan Douglas. This one work buttresses our conceptual art collection, landscape collection, and incorporates a new artist of color into the collection, all aspects of our photography collection that needed support. More recently, I acquired Fort Supply, a 24-panel monotype assemblage by Cheyenne artist Edgar Heap of Birds. For several years I’ve worked on bolstering our monotype holdings. In this case, Fort Supply enhances our important collection of color prints, brings another monotype intp the collection, and enriches our holdings of American Indian art, an area where WAM’s collection is thin.

Edgar Heap of Birds, Fort Supply, 2017, 24 monotypes on Rives BFK paper, Museum Purchase through the Eliza S. Paine Fund, the Chapin Riley Fund and the Ruth and Loring Holmes Dodd Fund, 2020.18, ©Edgar Heap of Birds

SS: In the world of print collecting, who gets collected and who is left out?

NB: I think that the canons of painting, sculpture, and photography sometimes prejudice who gets collected in the area of prints. Surveys of western art overwhelmingly privilege painting. As a result, some assume that the best painters make the best printmakers. Of course, this can be true; think of Durer, Rembrandt, Goya, and Degas for example. But that’s not usually the case. As a result, someone like Stanley William Hayter may get overlooked despite the fact that Hayter is one of the most important printmakers of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, this is a problem that’s unlikely to disappear until both the academy and museums make a point of dispelling a media hierarchy.

Added to all of this is a history that privileged and, in many ways, continues to privilege artists who are cis gendered, white men. Art schooling and apprenticeships in printmaking were almost exclusively limited to men until the second half of the nineteenth century. Further, pan-Atlantic art, perhaps somewhat understandably, consumes most of the real estate in many American encyclopedic and contemporary art museums. Who gets left out? Artists of color, women, and printmakers who lived and worked in South America, Southeast Asia, Africa, Russia, and Australia, to name just a few.

Mary Cassatt, The Fitting, 1891, drypoint, softground etching and aquatint, 37.5 x 25.7 cm, sheet, Mrs. Kingsmill Marrs Collection, 1926.199

SS: What is the value of working with original objects in a time when our screens are so saturated with images?

NB: It’s interesting how often I’m asked some variation on this question. I have to imagine it’s a question posed to lots of curators and no one has a perfect response. That said, I think that the pandemic has taught us a lot with regard to the value of the real versus the virtual. What’s the value of having dinner with friends versus a virtual evening of cocktails by Zoom? What’s the value of looking at a video of your nephew’s birthday versus being there in person? The video can tell you a lot, but it’s not the same as

being in the room when it happens. For me, both in the case of seeing my nephew and looking at art, it’s an intangible kind of intimacy which includes physical proximity and an emotional closeness.

Also, for me, objecthood matters. Seeing the way ink rests on the surface of a print betrays whether it is a reproduction or an original work. Oftentimes that doesn’t translate on a screen. The scale of a print, and the paper selected, inform our understanding of an artwork. A massive wall-sized Christiane Baumgartner woodcut can be presented on our screens at exactly the same size as a three-inch Edward Calvert wood engraving. Screens are useful tools but insufficient for understanding the physical world. It’s wonderful that the digital world offers us the opportunity to access art worldwide. It assists our research and lessens certain kinds of inequities that prevent people seeing works that are thousands of miles away. But at the end of the day smartphones, tablets, and computer screens are a two-dimensional platforms translating a three-dimensional world. Without a robust understanding of materials like paint, ink, wood, iron, fabric, paper, and the like, the virtual world is an empty point of reference.

Nancy Burns, on the left, examines a Hedda Sterne print

with paper conservator Eliza Spaulding